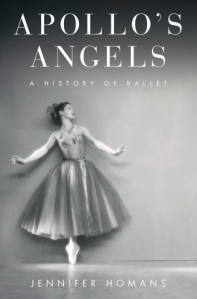

I was prompted to read Jennifer Homans’ Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet after hearing an interview with her on the radio. I am a little over half way in and I realized that the book is too brilliant to be summed up in one post, so I decided to give you bits and pieces of it along the way.

She mentioned this part from the introduction in the interview, and it’s the first of many stunning things I’ve read so far.

She mentioned this part from the introduction in the interview, and it’s the first of many stunning things I’ve read so far.

“And yet it is because ballet has no fixed texts, because it is an oral and physical tradition, a storytelling art passed on, like Homer’s epics, from person to person, that it is more and not less rooted in the past. For it does have texts, even if these are not written down: dancers are required to master steps and variations, ritual and practices […] The teachings of the master are revered for the beauty and logic, but also because they are the only connection the younger dancer has to the past – and she knows it. […]

Ballet, then is an art of memory, not history.” p. xix

From chapter 1: France and the Classical Origins of Ballet

“Nor is it a coincidence that the younger Louis [XIV] – more than any other kind before or since – devoted himself so passionately to dancing. Making his debut in 1651 at age thirteen, Louis danced roles in some forty major productions until his final appearance eighteen years later in the Ballet de Flore of 1669. […] Every morning following the ceremonial lever, he retired to a large room where he practiced vaulting, fencing, and dancing. His training was directed by his personal ballet master, Pierre Beauchamps, who worked with the king daily for more than twenty years. […]

Louis’s interest in ballet was no just a youthful fling; it was a matter of state.As he himself later reflected, these performances flattered his courtiers and captured the hearts and minds of his people, “perhaps more strongly, even, that gifts or good deeds.”p. 11, 12

The best part regarding Louis XIV comes when Homans is describing all the etiquette at the king’s court from which ballet arose and what initially made ballet so important. “As Madame de Maintenon once quipped, “The austerities of a convent are nothing compared to the austerities of etiquette to which the Kin’s courtiers are subjected.” But Louis knew what he was doing. “Those people are gravely mistaken,” he warned, “who imagine that all this is a mere ceremony.” ” p. 15

From chapter 2: The Enlightenment and the Story of Ballet

Meet Marie Sallé (c. 1707 – 1756). “What are we to make of Sallé? In one sense, she was nothing more than a fairground performer who had the luck of great beauty and a considerable discipline: she put herself through rigorous practice sessions daily. But she was also more than this, and deserves our attention because she was one of the first women to intuitively play sex and ballet off each other and to set her talents against convention.” p. 62

“Sallé’s Parisian contemporary and rival Marie-Anne de Cupis de Camargo (1710 – 1770), known as La Camargo, found a different way out of the staid conventions of her art: technical brilliance. Women did not traditionally perform the jumps, beats, and other virtuosic steps […] Camargo did. She did not stop there but went so fas as to shorten her skirts to the calf so that her brilliant footwork (and sexy feet) might be better appreciated […].” p.63

“Between them, Sallé and Camargo inadvertently shifted the course of ballet and pointed it toward the nineteenth century, when the ballerina would eventually displace the danseur at the summit of the art.” p. 63

The story also deeply concerns people like Jean-Georges Noverre (1727 – 1810) who was a ballet master who worked in Paris, Lyon, London, Berlin, Stuttgart, Vienna and Milan. And also people like Charles Eugene, Duke of Württemberg of Stuttgart who was “handsome, intelligent, and autocratic, ” “loved women and ballet, and had a strong taste for French and Italian music and art.” p. 81. Not just because ballet masters created new dances and techniques and moved the story of ballet forward, but because they followed the money. When the Duke of Württemberg went broke in 1768 and could no longer support his big ballet troupe, the dancers and Noverre had to go elsewhere, thus disseminating their art. This made ballet spread across Europe and cross-polinated various techniques, dances, choreographies, styles, musics, enriching them in the process.

to be continued…