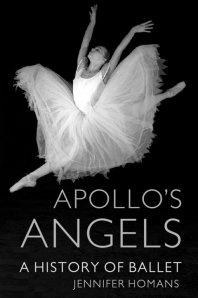

Ballet is a huge, gaping hole in my education. I’ve been to a handful in my life. What made me read this book is the radio interview I heard on the radio with the author, Jennifer Homans. It was three things she said: 1) That ballet has an oral history and no fixed texts; 2) That this is the first comprehensive history of ballet ever! and 3) that ballet might be dying.

Ballet is a huge, gaping hole in my education. I’ve been to a handful in my life. What made me read this book is the radio interview I heard on the radio with the author, Jennifer Homans. It was three things she said: 1) That ballet has an oral history and no fixed texts; 2) That this is the first comprehensive history of ballet ever! and 3) that ballet might be dying.

It goes without saying that the whole time I was reading the book I wanted to run out and go see a ballet. But even if I never see another ballet in my life, it would be worth reading this book for its cultural history, its scope and breadth of subject, and the brilliance of thinking that comes through in Homans’ clear writing. Frankly, reading this book has been humbling. Nothing disabuses one of erroneous beliefs and conceits of one’s time like a good history book.

One of the most fascinating things about the book is Homans’ clear grasp and exposition of all the twists and turns of history and the multiplicity of factors that go into a single cultural phenomenon. (To start with the second part there,) how classical ballet originates with French court etiquette, but is almost immediately set in a productive and fertile opposition with low entertainment like pantomime; how it is the body language of the rich, but can also be learned by the poor to move up in society. This theme crops up over and over in the book.

Homans shows (this is the first part of that sentence above) how things build on their past by breaking with it. How a direct descendant of a teacher might in fact be straying away from a tradition, and how someone desperately trying to get away from form of art, consciously or unconsciously incorporates the past, and ties it to their own work. How sometimes looking toward the past can be more radical than blindly trying to force one’s way into the future. And most cruelly, how the accomplishments of the day can mean nothing to the future often flaring and falling away, while things of the moment considered passé and démodé can turn out to be long-lasting. History, as Engels put it, is the cruelest of all the goddesses.

Not that everything always has to be measured by whether it lasts, but there is something satisfying (to me at least) how individual cultural or national traditions seemingly die out in their place of origin, only to show up woven into the national tradition of another. This idea of layering of traditions, techniques, of the language of an art and craft. When it seems to be lost in France it moves to Denmark, and just when it seems to go stale in Denmark, the Danish steps appear in the bodies of Russian dancers, etc.

Another thing that drew me to the book are my own affinities of thinking and talking about the body. How a four hundred year tradition, and a world wide art form can be seen in the body of the performer. For every great dancer in the book, Homans is able to find incredible ways of describing how their body incorporates the grammar of dance and then say something. Not with words, but with the body and movement. In the chapter on America she talks about the dancer Nora Kaye she says that she “had this kind of body, naturally opaque and without luminosity or grace.” Then talking about Balanchine’s dancers, she says that “what they did share was an unusual physical luminosity.”

The body, then, is the written text of ballet. Nor has using recording devices changed this. As she points out at the end, watching a video of someone dancing can be helpful, but it is in itself a translation of a three-dimensional form onto a two dimensional surface that then has to be retranslated back into three dimensions. Further, a video recording does not distinguish between accident and mistake: when an unforeseen thing gets incorporated into the ballet, and when it is simply discarded in future performances. Not to mention that the video is a record of a single performance, whereas a ballet can be said to be like a jazz standard, more a compilation of all the performances, variations, attempts together, rather than any single ‘definitive’ one.

So what of this claim that ballet is dying? First of all she seems to be too harsh a critic of contemporary dancers and choreographers. (If I were a dancer today I would be afraid of having her in the audience.) Secondly, perhaps her looking so far back into the past and so hard at the luminaries of the yesterday has rendered her a bit blind to the lights of today. I don’t know enough ballet to be able to say at all, nor can I vouch that the pessimism in the epilogue is not just Homans’ (particularly strong) conservatism. Who knows? But she does, herself, open the door at the end. If Balanchine is the crown jewel in the ballet tradition thus far, maybe we need someone to do something in opposition to him, to kick start another productive dynamic of history. Maybe the opposition will come between ballet’s Western tradition (here I include Russia in a broad idea of the West) and the rise of India, China, Brazil? Maybe the opposition will be a class one. If the history of ballet thus far has been a wresting of the art from the hands of the aristocracy into the hands of the bourgeoisie – a feat not fully accomplished until ballet moved into the English-speaking world and the twentieth century – perhaps in opposition to this bourgeois form there will be one of the working class…don’t let me get too Marxist on you (I already quoted Engels).

Well, I need to stop somewhere. Over at her website, the photographer Paula Lobo, has beautiful black and white photos of dancers. I thought I would share some with you here.

.

.

Leave a comment